Czech language

| Czech | ||

|---|---|---|

| Čeština, Český jazyk | ||

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Central Europe | |

| Total speakers | 12 million | |

| Ranking | 70 | |

| Language family | Indo-European | |

| Writing system | Czech variant of Latin alphabet | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | ||

| Regulated by | Czech Language Institute | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | cs | |

| ISO 639-2 | cze (B) | ces (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ces | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Czech (pronounced /ˈtʃɛk/; čeština Czech pronunciation: [ˈt͡ʃɛʃcɪna]) is a West Slavic language with about 12 million native speakers; it is the majority language in the Czech Republic and spoken by Czechs worldwide. The language was known as Bohemian in English until the late 19th century. Czech is similar to and mutually intelligible with Slovak and, to a lesser extent, to Polish and Sorbian.

Contents |

Official status

Czech is widely spoken by most inhabitants of the Czech Republic. As given by appropriate laws, courts and authorities act and make out documents and executions in the Czech language (financial authorities also in the Slovak language). Czech can be used in all official proceedings also in Slovakia as granted by Article 6 of Slovak Minority Language Act 184/1999 Zb.

People who do not speak Czech have the right to get an interpreter. Instructions for use in Czech must be added to all marketed goods. Regarding knowledge of other languages in the Czech Republic, English and German are the most common foreign languages studied and used. Russian is also spoken, but to a much lesser extent than it was prior to the fall of Communism.

The right to one's own language is guaranteed by the Constitution for all national and ethnic minorities.

Czech is also one of the 23 official languages in the European Union (since May 2004).

Mutual intelligibility

Speakers of Czech and Slovak usually understand both languages in their written and spoken form, thus constituting a pluricentric language, though some dialects or heavily accented speech in either language might present difficulties to speakers of the other (in particular, Czech speakers may find Eastern Slovak dialects difficult to comprehend). Younger generations of Czechs living after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993 (therefore generally less familiar with Slovak) might also have some problems with a certain number of words and expressions which differ considerably in the two languages, and with false friends. Nevertheless, these differences do not impede mutual intelligibility significantly.

Name

The name "čeština", Czech, is derived from a Slavic tribe of Czechs ("Čech", pl. "Češi") that inhabited Central Bohemia and united neighbouring Slavic tribes under the reign of the Přemyslid dynasty ("Přemyslovci"). The etymology According to a legend, it is derived from the Forefather Čech, who brought the tribe of Czechs into its land. The variant English name "Bohemian" was used until the late 19th century, reflecting the original English name of the Czech state derived from the Celtic tribe of Boii who inhabited the area since the 4th century BC.

History

The Czech language developed from the Proto-Slavic language at the close of the 1st millennium.

Phonology

The phonology of Czech may seem rebarbative to English speakers as some words do not appear to have vowels: zmrzl (frozen solid), ztvrdl (hardened), scvrkl (shrunk), čtvrthrst (quarter-handful), blb (fool), vlk (wolf), or smrt (death). A popular example of this is the phrase "strč prst skrz krk" meaning "stick a finger through your throat" or "Smrž pln skvrn zvlhl z mlh." meaning "Morel full of spots was dampened by fogs". The consonants l and r can function as the nucleus of a syllable in Czech, since they are sonorant consonants. A similar phenomenon also occurs in American English, where the reduced syllables at the ends of "butter" and "bottle" are pronounced [ˈbʌɾ.ɹ] and [ˈbɒɾ.l], with syllabic consonants as syllable nuclei. It also features the consonant ř, a phoneme that is said to be unique to Czech. To a foreign ear, it sounds very similar to [ʒ], though a better approximation could be rolled (trilled) [r] combined with [ʒ], which was incidentally sometimes used as an orthography for this sound (rž) for example in the royal charter of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor from 1609. The phonetic description of the sound is a raised alveolar non-sonorant trill which can be either voiceless (terminally or next to a voiceless consonant) or voiced (elsewhere), the IPA transcription being [ r̝ ].

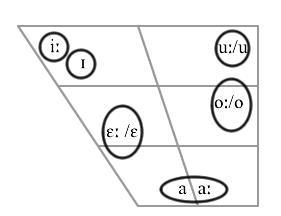

Vowels

There are 10 vowels in Czech which are regarded as individual phonemes. There are 5 short and 5 long vowels.

Long vowels are indicated by an acute accent or a ring.

- /iː/ is represented by letters í and ý

- /uː/ is represented by letters ú and ů

- /ɛː/ is represented by letter é

- /aː/ is represented by letter á

- /oː/ is represented by letter ó

Short vowels

- /ɪ/ is represented by letters i and y

- /u/ is represented by letter u

- /ɛ/ is represented by letter e (and sometimes ě)

- /a/ (actually an open central unrounded vowel [ä]) is represented by letter a

- /o/ (actually a mid back rounded vowel [o̞]) is represented by letter o

There have been some disputes as to whether there are really ten or only five vowels in Czech. These can however be settled by a simple list of minimal pairs:

- sad [sat] ~ sát [saːt]

- bal [bal] ~ bál [baːl]

- kaž [kaʃ] ~ káš [kaːʃ]

- lek [lɛk] ~ lék [lɛːk]

- len [lɛn] ~ lén [lɛːn]

- sled [slɛt] ~ slét [slɛːt]

- bor [bɔr] ~ bór [bɔːr]

- chor [xɔr] ~ chór [xɔːr]

- mot [mɔt] ~ mód [mɔːt]

- sir [sɪr] ~ sýr [siːr]

- Žid [ʒɪt] ~ žít [ʒiːt]

- kil [kɪl] ~ kýl [kiːl]

- dul [dul] ~ důl [duːl]

- nuž [nuʃ] ~ nůž [nuːʃ]

- ruš [ruʃ] ~ růž [ruːʃ]

- kura [kura] ~ kůra [kuːra] ~ kúra [kuːra]

Note that ě is not a separate vowel. Analogous to y, ý and ů, it is a grapheme kept for historical reasons (see Czech orthography).

/r/ and /l/ (and sometimes also /m/ and /n/) can be syllabic, i.e. they can take the vowel's role as the nucleus of a syllable, e.g. vlk (wolf).

Diphthongs

There are three diphthongs in Czech:

- /aʊ̯/ represented by au (almost exclusively in words of foreign origin)

- /eʊ̯/ represented by eu (in words of foreign origin only)

- /oʊ̯/ represented by ou

When these groups come together at morpheme boundaries, they do not form diphthongs in standard Czech; for instance naučit, neučit, poučit ([-au-, -eu-, -ou-] or [-aʔu-, -eʔu-, -oʔu-]). Vowel groups ia, i.e., ii, io, and iu in foreign words are likewise not regarded as diphthongs; they may also pronounced with /j/ between the vowels [ɪja, ɪjɛ, ɪjɪ, ɪjo, ɪju].

Consonants

| Place of articulation → | Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manner of articulation ↓ | Bilabial | Labio‐ dental |

Alveolar | Post‐ alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | ||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | c ɟ | k ɡ | (ʔ) | |||

| Affricate | t͡s (d͡z) | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | x (ɣ) | ɦ | |||

| Approximant | j | |||||||

| Trill | r r̝* | |||||||

| Lateral Approximant | l | |||||||

* [r̝] is a specific raised alveolar non-sonorant trill which can be pronounced both voiced and voiceless (regarded as two allophones of one phoneme).

The consonants in parentheses are regarded as allophones of other consonants:

- [ŋ] is an allophone of /n/ when preceding velar consonants (/k/ and /ɡ/).

- [ɣ] is a voiced allophone of /x/ when preceding a voiced consonant

- [d͡z] is an allophone of /t͡s/ when preceding a voiced consonant

The glottal stop [ʔ], which appears as a separator between two vowels or word-initially before a vowel, is not considered a separate phoneme or an allophone of one.

- /ʃ/ is represented by the letter š

- /ʒ/ is represented by the letter ž

- /ɲ/ is represented by the letter ň

- /c/ is represented by the letter ť

- /ɟ/ is represented by the letter ď

- /ɦ/ is represented by the letter h

- /x/ is represented by the digraph ch

- /ts/ is represented by the letter c

- /tʃ/ is represented by the letter č

- /dʒ/ is represented by the digraph dž

- /r̝/ is represented by the letter ř

The other consonants are represented by the same characters (letters) as in the IPA.

(See also: Czech alphabet)

Stress

The primary stress is always fixed to the first syllable of a stressed unit, which is usually identical to a word. The exceptions are:

- Monosyllabic prepositions form a unit with following words (if the following word is not longer than three syllables). The stress is placed on the preposition: e.g. ˈPraha (Prague) --> ˈdo Prahy (to Prague). This does not apply to long words, e.g. ˈna ˈkoloˌnádě (on the (spa) walk).

- Some monosyllabic words (e.g. mi (me), ti ((to) you), to (it), se, si (oneself), jsem (am), jsi (are), etc.) are clitics — they are not stressed and form a unit with preceding words. A clitic cannot be the first word in a sentence, because it requires a preceding word to form a unit with. Example: ˈNapsal jsem ti ˈten ˈdopis, I have written the letter to you.

Long words have secondary stress, which is usually placed on every odd syllable, e.g. ˈnej.krás.ˌněj.ší (the most beautiful).

Stress in Czech denotes boundaries between words, but does not distinguish word meanings. It also has no influence on the quality or quantity of vowels. Vowels are not reduced in unstressed syllables and both long and short vowels can occur in either stressed or unstressed syllables.

Syntax and Morphology

As in most Slavic languages, many words (especially nouns, verbs and adjectives) have many forms (inflections). In this regard, Czech and the Slavic languages are closer to their Indo-European origins than other languages in the same family that have lost much inflection. Moreover, in Czech the rules of morphology are extremely irregular and many forms have official, colloquial and sometimes semi-official variants.

Word order

The word order in Czech serves similar function as sentence stress and articles in English. Often all the permutations of words in a clause are possible. While the permutations mostly share the same meaning, they differ in the topic-focus articulation.

For example: Češi udělali revoluci (The Czechs made a revolution), Revoluci udělali Češi (It was the Czechs who made the revolution), and Češi revoluci udělali (The Czechs did make a revolution).

Parts of speech

- Noun (podstatné jméno)

- Adjective (přídavné jméno)

- Pronoun (zájmeno)

- Numeral (číslovka)

- Verb (sloveso)

- Adverb (příslovce)

- Preposition (předložka)

- Conjunction (spojka)

- Particle (částice)

- Interjection (citoslovce)

Nouns, adjectives, pronouns and numbers are declined (7 cases over a number of declension models) and verbs are conjugated; the other parts of speech are not inflected (with the exception of comparative formation in adverbs).

Dialects

In the Czech Republic two distinct variants or interdialects of spoken Czech can be found, both corresponding more or less to geographic areas within the country. The first, and most widely used, is "Common Czech", spoken especially in Bohemia. It has some grammatical differences from "standard" Czech, along with some differences in pronunciation. The most common pronunciation changes include -ý becoming -ej in some circumstances, -é becoming -ý- in some circumstances (-ej- in others). Also, noun declension is changed, most notably the instrumental case. Instead of having various endings (depending on gender) in the instrumental, Bohemians will just put -ama or -ma at the end of all plural instrumental declensions. Currently, these forms are very common throughout the entire Czech republic, including Moravia and Silesia. Also pronunciation changes slightly, as the Bohemians tend to have more open vowels than Moravians. This is said to be especially prevalent among people from Prague.

The second major variant is spoken in Moravia and Silesia. Nowadays it is very close to the Bohemian form of Common Czech. This variant has some words different from its standard Czech equivalents. For example in the dialect spoken in Brno, tramvaj (streetcar or tram) is šalina (originating from German "ElektriSCHELINIE"). Unlike in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia tend to have more local dialects varying from place to place, however just as in Bohemia, most have been already heavily influenced and mostly replaced by Common Czech. Everyday spoken form in Moravia and Silesia would be a mixture of remnants of old local dialect, some Standard Czech forms and especially Common Czech. The most notable difference is a shift in used prepositions and case of noun, for example k jídlu (to eat - dative) (as in German zum Essen) becomes na jídlo (accusative), as it is in Slovak na jedlo. It is a common misconception that the use of Standard Czech in everyday situations is more frequent than in Bohemia. The Standard Czech became standardized by the Czech national revivalists in the 19th century, based on an already three hundred year old translation of the Bible (Bible of Kralice) using an older variant of the then-current language (for example, preferring -ý- to -ej-). These Standard forms are still common in spoken language both in Moravia and Silesia. Some Moravians and Silesians therefore tend to say that they use "proper" language, unlike their Bohemian compatriots.

A special case is the Cieszyn Silesian dialect, spoken in Cieszyn Silesia (Těšínsko), which is a transitional dialect between the Czech and Polish languages.

It should be noted that some south Moravian dialects are also sometimes, although rarely, considered (also by Czech linguists in the 90's or later, e.g. Václav Machek in his "Etymologický slovník jazyka českého", 1997, ISBN 80-7106-242-1, p. 8, who speaks about a "Moravian-Slovak" dialect from the region of Moravian "Slovácko") to be actually dialects of the Slovak language, which has its roots in the Moravian empire when Slovaks and Moravians were one nation (without Bohemians) with one language. Those dialects still have the same suffixes (for inflected substantives and pronouns and for conjugated verbs) as Slovak.

The minor dialect spoken in Pilsen and parts of Western Bohemia and in wester parts of former Prachens region differs, among other things, by intonation of questions: all the words except for the last word of a sentence have a high pitch. This is the reason why the people from Pilsen are said to be "singing". Words that start questions are often given an additional "-pa": "Kolipa je hodin?" (regular Czech: "Kolik je hodin?"; English: "What time is it?"). The words like "this" (regular Czech: "tento/tato/toto") are often replaced by "tuten/tuta/tuto"); some examples: "What is this? or "What's happening?" is "Copato?" instead of "Co se stalo? / Co je to?" or "Why?" is "Pročpa?" instead of "Proč?". The region of Chodsko is the home of a very special Czech-Polish dialect of the Chods people who were displaced in about the 10th century from Silesia owing to the protection of the western border of Bohemia.

Declension

Czechs typically refer to the noun cases by number and learn them by means of the question to which they are the answer. These numbers do not necessarily correspond to numbered cases in other languages (e.g., the Slovene locative and instrumental are known as the 5th and 6th cases). When learning a new word, Czech children recite the cases using a set of example phrases, shown as follows:

| 1. | kdo/co? (who/what?) | nominative |

| 2. | bez koho/čeho? (without whom/what?) | genitive |

| 3. | ke komu/čemu? (to whom/what?) | dative |

| 4. | vidíme koho/co? (We see whom/what?) | accusative |

| 5. | oslovujeme/voláme (I address/call) | vocative |

| 6. | o kom/čem? (about whom/what?) | locative |

| 7. | s kým/čím? (with whom/what?) | instrumental |

The case used depends on a number of variables.

Prepositions with certain cases

The simplest of the rules governing noun declension is the use of prepositions (předložky). Excepting expressions and common phrases, each preposition is matched with a certain noun declension case depending on use. The following are basic examples of common prepositions and their corresponding noun cases (note: these examples represent only one circumstance. Often each preposition can be used with two or more noun cases depending on the sentence).

- Genitive: během (during), podle/dle (according to/along), vedle (beside), kolem (around), okolo (around), do (into), od(e) (away from), z(e) (out of/from), bez(e) (without), místo (instead of), u (at/by the).

- Dative: k(e) (towards), proti (against), díky (thanks to), naproti (opposite).

- Accusative: skrz(e) (through), pro (for), na (to/for).

- Locative: o (around, about), na (on), při (into, in, around), v (in), po (after, around).

- Instrumental: za (behind), před (in front of), mezi (between), pod(e) (below), s(e) (with), nad(e) (above).

Many of the above prepositions are used in different circumstances. For instance, when motion or a change of position is expressed, prepositions like nad, mezi, na, pod, etc. are used with the accusative case.

The second factor affecting noun declension is the verb used. In Czech grammar, the accusative case serves as the direct object, and the dative case serves as the indirect object. Some verbs require the genitive case to be used. For example, the verb "zeptat se" (to ask) requires that the person being asked the question be in the genitive case (Zeptat se koho/čeho), and that the thing being asked about follow the preposition "na" and be in the accusative case (Zeptat se koho/čeho na koho/co).

Counting and declension

The third factor affecting noun declension is number. Czech has a typical Slavic counting system, explained as follows with the example masculine animate noun muž (man):

- For the number one, the singular number is used: jeden muž.

- For the numbers 2, 3, and 4, any case may be used, depending on the function of the noun in the sentence: dva muži (nominative). "Vidím dva muže" (accusative).

- For all numbers from 5 on, the genitive plural is used when the noun would normally be in the nominative, accusative or vocative case: pět mužů. "Pět mužů je tam." Five men are over there. "Vidím pět mužů." I see five men. For other cases, however, the noun is not placed in the genitive. "Nad pěti muži." Above the five men (instrumental).

The example above shows colloquial use. In literary use, there is an additional rule: The above system is based only on the last word of the number. Thus a number like 101 uses the singular (sto jeden muž) and 102 uses the ordinary plural (sto dva muži). For numbers that can be read in two ways, such as 21, the grammar may depend on which one is chosen (dvacet jeden muž or jednadvacet mužů). This system is becoming less common and is not used in everyday speech, as well as becoming harder to find in modern literature.

Numbers have declension patterns in Czech. The number two, for instance, declines as follows:

| Nominative | dva/dvě |

| Genitive | dvou |

| Dative | dvěma |

| Accusative | dva/dvě |

| Vocative | dva/dvě |

| Locative | (o) dvou |

| Instrumental | dvěma |

The numbers are singular (jednotné číslo), plural (množné číslo), and remains of dual. The number two, as declined above, is an example of the now-diminished dual number. The dual number is used for only certain human body parts: hands, shoulders, eyes, ears, knees, legs, and breasts. In all but two of the above body parts (eyes and ears) the dual number is only vestigial and affects very few aspects of declension (mostly the genitive and prepositional cases). However, in Common Czech this dual ending of the instrumental case is used as the regular instrumental plural form, for example, s kluky (with the boys) becomes s klukama, and so on for all nouns.

Gender

The three genders are masculine, feminine, and neuter, with masculine further subdivided into animate and inanimate. Words for individuals with biological gender usually have the corresponding grammatical gender, with only a few exceptions; similarly, among the masculine nouns, the distinction between animate and inanimate also follows meaning. Other words have arbitrary grammatical genders. Thus, for instance, pes (dog) is masculine animate, stůl (table) is masculine inanimate, kočka (cat) and židle (chair) are feminine, and morče (guinea-pig) and světlo (light) are neuter.

Tenses and conditionals

Compared to English or Romance languages, Czech has a rather simple set of tenses. They are present, past, and future.

Past is used in almost all instances of past action, and replaces every past tense in English (past simple, past perfect and in some cases the present perfect). The past tense is usually formed by affixing an -l- on the end of the verb, sometimes with a minor (rarely significant) stem change. After adding the -l-, letters are added in order to agree with the subject (-a for feminine, -o for neuter, -i, -y or -a for plural).

The present tense is also used to describe ongoing actions which continue to the present, where in English a present perfect would be used, for instance, "I've been doing this for three hours". In Czech, as there is no present perfect tense, the present indicative is used and is directly translated as "I do this for three hours". However, when the present perfect is used to denote past actions without a time reference (e.g. "I've been to Italy three times"), the past tense would be used.

There are also sometimes second forms of certain verbs (like to go, to do, etc.) that indicate a habitual or repeated action. These are known as iterative forms. For instance, the verb jít (to go by foot) has the iterative form chodit (to go regularly).

There is also no tense shifting (as in reported speech). E.g. "He loves her" -> "He said he loved her", the time is shifted from present to past. In Czech it is "Má ji rád" -> "Řekl, že ji má rád". The "má rád" implies present tense in both cases.

The future tense is another fickle part of Czech grammar. Often, present tense verbs are only used to denote future actions. For instance, the verb "vyhodit" (throw out) appears like a normal present tense, but actually indicates a future action. Vyhodit is actually a modified form of the verb "hodit" (to throw), with the prefix "vy-" added. The addition of such prefixes almost always changes the aspect of the verb to the perfective aspect. This form of the verb indicates a completed action, so either the action is already completed (past) or yet to be completed (future). A different form, "vyhazovat", indicates an ongoing action (imperfective aspect) and has all three tenses.

Many verbs in the Czech language undergo such modifications, allowing a single verb to spawn multiple meanings.

Maps & Samples

Slavic languages |

Official usage of Czech language in Vojvodina, Serbia |

Sample (1846) |

See also

- Czech alphabet

- Czech Centers

- Czech declension

- Czech name

- Czech orthography

- Orthographia bohemica

- Czech phonology

- Czech verb

- Czech word order

- Háček

- Swadesh list of Slavic words

References

External links

- Czech language at Ethnologue

- (Czech) Ústav pro jazyk český - Czech Language Institute, the regulatory body for the Czech language

- Reference Grammar of Czech, written by Laura Janda and Charles Townsend

- English-Czech /Czech-English Online Dictionary

- Czech Monolingual Online Dictionary

- Czech National Corpus

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||